My Story | Ghana, Memory, and the Work of Preservation

by Brandon Nightingale | PhD Student | History

This past spring break, I had the transformative opportunity to travel to Ghana as part of a Howard University History and Culture Tour. Over ten days, I journeyed alongside fellow scholars to explore the historical, spiritual, and cultural landscapes of Accra, Kumasi, and Cape Coast. While the trip offered many unforgettable moments—walking through the bustling art markets, engaging with artisans in the craft villages of Bonwire and Ntonso, and reflecting on the legacies of Pan-African leaders—it was more than a visit. For me, it was a return. A return to ancestral memory, to Pan-African heritage, and to the archival impulses that guide my academic and professional work.

I joined the program as a teaching assistant with the Department of History, supporting our undergraduate students who participated in this study abroad experience. It was incredibly meaningful to connect with students preparing to graduate with their degrees in history—many of whom reminded me of my own journey through the discipline. Our conversations on the bus, during site visits, and over shared meals were powerful reminders that historical study is not just academic—it’s personal, communal, and alive.

Equally enriching was the chance to travel alongside three fellow History PhD students, deepening our bonds through reflection, laughter, and the shared awe of discovering our roots. One of the highlights was engaging in rich conversations with Dr. Kay Wright-Lewis, whose mentorship and insight helped frame the experience through a lens of Black historical resilience and reclamation.

The team from African Loom Tours also played a vital role in shaping our experience. Their knowledge, care, and cultural context enriched every site we visited. From navigating city traffic to facilitating discussions on Asante history, their guidance made the learning tangible, immersive, and unforgettable.

One of the most exhilarating moments was visiting Kakum National Park, home to one of the few remaining rainforests in West Africa. Suspended over 100 feet above the forest floor, I crossed the iconic canopy bridges that offer a breathtaking view of Ghana’s natural landscape. With each careful step across the swaying walkway—and Dr. Benjamin Talton just behind me—I reflected on how this experience mirrored the very work we do in archives: moving forward with care, even when the ground beneath us feels uncertain.

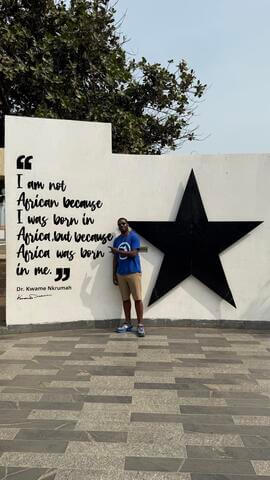

The power of this trip was amplified by my current coursework. This semester, I’m taking Pan-Africanism: Past and Present (AFST-215-01) with Professor Amsale Alemu. A month before the trip, I led a class discussion on Kwame Nkrumah’s political vision. To then stand before his mausoleum in Accra was a full-circle moment—one that reminded me how Pan-African thought is not just to be studied, but lived. That moment held even more meaning knowing that Nkrumah was also a member of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.—a bond we share. While in Ghana, I had the special opportunity to connect with several brothers from the local chapter, further grounding this international experience in community and legacy.

As a graduate student deeply engaged in research on the Black press and Pan-African intellectual history, Ghana is not merely a geographic site—it’s a living archive. Visiting the W.E.B. Du Bois Center for Pan-Africanism and the Nkrumah Mausoleum offered physical proximity to thinkers whose writings and legacies I regularly encounter in the classroom and in the stacks. Their lives, etched into monuments and memory, reminded me that decolonial scholarship must remain tethered to lived histories and local contexts.

Beyond my studies, I serve as the Project Manager for the Black Press Archives Digitization Project at Howard’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. In this role, I’m responsible for stewarding the digitization of historically Black newspapers, including publications that span the African continent. Being in Ghana reinforced the urgency of that work. When we visited Bonwire, the birthplace of Kente weaving, and Ntonso, where Adinkra symbols are hand-stamped onto cloth, I was reminded that preservation is not just technical—it is cultural. The care artisans take in creating each piece mirrors the commitment we must bring to preserving African diasporic media heritage.

Every site we visited reaffirmed for me that archival work is never neutral. We are not just scanning papers; we are resurrecting voices, protecting truths, and reconnecting fragmented narratives. Traveling through Ghana as a Howard scholar and as a steward of memory reminded me of the stakes of our work and the beauty of our collective resilience.

This trip to Ghana has made me a more grounded researcher, a more empathetic archivist, and a more intentional descendant. It was not a detour from my work—it was a deepening of it.

Nante Yie, Ghana. I’ll be back.