My Story | Dr. Tiffany Wheatland-Disu

by Dr. Tiffany Wheatland-Disu | Doctoral Alumni

Conducting archival research in Guinea, West Africa during the summer of 2023 was a profoundly enriching experience. Motivated by President Kwame Nkrumah’s 1958 convening of the All-African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana, my research explored the transnational dimensions of radical thought and praxis it inspired. My dissertation, A History of the All-African People's Revolutionary Party (A-APRP) 1968-1998: A Pivotal Moment in Black Internationalism examines how the shared vision of radical pan-Africanism of Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah, Guinean President Sékou Touré and Trinidadian-born Black Power advocate Kwame Ture, formerly known as Stokely Carmichael, led to the founding the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP)—one of the most significant transnational, political formations of the twentieth century.

A scholar of Black internationalism, I was keen to understand the commonalities and connections between 20th century anti-imperial, anti-colonial struggles and the forms of internationalism that emerged across West Africa and the broader Atlantic world. I was particularly interested in understanding the role of Ghana and Guinea as sites Black internationalist ferment during the eras of decolonization (1945-1975) and the Cold War (1947-1989). Through the study of History, I developed a deep appreciation of interdisciplinary approaches to reconstructing the past. My academic training—spanning History, African Studies, Political Science and Women’s Studies, prepared me for the task of conducting original research using various approaches. Interdisciplinary research also enabled me to integrate diverse forms of knowledge and to consider varied methodologies for historical reconstruction and interpretation. Readings courses with my dissertation advisor, Dr. Jean-Michel Mabeko-Tali—a renowned scholar of African history, deepened my knowledge African epistemology creating space to decenter, critique and challenge the dominance of Eurocentric frameworks.

Drawing inspiration from the work of current and former Howard University faculty, I designed my study to engage a multi-archival, multi-national review of sources collected from archives in Guinea, Ghana and the U.S. and oral histories conducted with affiliates of the A-APRP and Parti Démocratique de Guinée (PDG). My research began at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, in the Kwame Nkrumah Papers and the Dabu Gizenga Collection on Kwame Nkrumah. These invaluable collections offered substantial evidence of Ghana’s internationalist vision and praxis of radial pan-Africanism, enabling me to chart the evolution of Nkrumah’s political thought and to map the trajectory of his radicalization. They also revealed the broader contours of the radical pan-Africanism shared by Ghana and Guinea, highlighting the revolutionary solidarity which existed between their respective leaders.

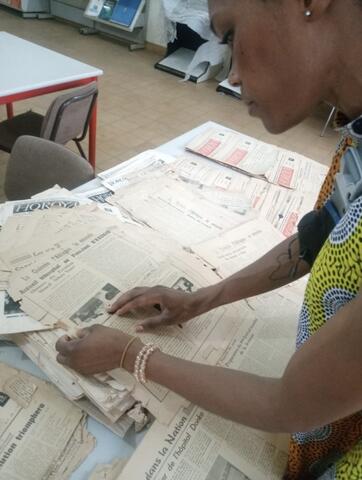

My research in Guinea confirmed that while both archival records and oral sources play a vital role in historical reconstruction and interpretation, each presents significant limitations. Archival records often reflect and reinforce hegemonic narratives that distort or suppress historical memory, and issues of bias and reliability can complicate the use of oral, memory-based sources. Historical narratives must therefore be critically examined and verified through a combination of published and unpublished primary documents and oral sources. Despite efforts to suppress, erase and distort evidence of Guinea’s radical history, a review

of national newspapers, La Liberté and Le Horoya housed at Les Archives Nationales, and the Kwame Ture Papers presided over by the Kwame Ture Estate, provided important insights into the fraternal bond between these two countries, underscoring Guinea’s role as a site of revolutionary ferment and refuge for African liberation movements during President Sekou Touré’s First Republic (1958-1984). However, given the extensive destruction of archival materials both in post-revolutionary Guinea and Ghana, and the enduring influence of hegemonic historical narratives, I found it necessary to augment my archival research with oral interviews. Archival destruction and poor preservation can severely hinder access to critical records. Fortunately in Guinea, the history of radical pan-Africanism is not only preserved in national archives, it can be observed in the streets of rural and urban spaces. It is distilled through dialogue and engagement with youth, elders, and everyday people.

In the field, each challenge also presents new possibilities. Guinea provided the foundation for leveraging oral histories to mitigate the effects of archival voids—gaps and silences in the historical record and acts of historical erasure. Recognizing the value of written and oral sources, I adopted the perspective of Joseph Ki-Zerbo, editor of the UNESCO General History of Africa series who argued that no single source should, on its own, be regarded as inherently superior. Through Howard University networks connecting continental and diaspora Africans, I conducted oral histories with historical actors whose insights enriched, complicated and clarified important aspects of my study. These narratives, complimented by historical records, proved indispensable in reconstructing and affirming Guinea’s legacy of radical pan-Africanism and in reinscribing the history of the A-APRP into the cannon of black radical thought.